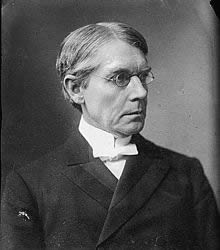

| Presbyterian minister the Rev. Francis Landey Patton rose up through the ranks of academia to become president of Ivy League school Princeton University — an achievement that no other Bermudian has matched. Patton was appointed president of Princeton University in New Jersey in 1888, served in the post for 14 years and contributed to its transition from a denominational college to a top-ranked university.

The Princeton presidency one of several high points during his 50-year career as a theologian, author and educator — and unapologetic conservative — in the United States.

But Patton, after whom Francis Patton School is named, remained a Warwick man at heart and he would retire to Bermuda at the end of his illustrious career.

Fortune

Descended from a long line of seafarers, Patton was the eldest of three sons of George Patton, a sea captain, who used a portion of the fortune he earned from a life on the high seas to purchase Carberry Hill, on Keith Hall Road, Warwick, as his family home.

Patton was born and raised at Carberry Hill — a property that remains in the Patton family today — and attended Warwick Academy. He received his religious education at Christ Presbyterian Church in Warwick, where Rev. Marischal Keith Frith became a major influence and the inspiration for his future calling as a minister.

Ordained

Patton attended boarding school in Ontario, Canada, and began his theological studies at Knox College, at the University of Toronto.He subsequently transferred to Princeton Theological Seminary in Princeton, New Jersey, from which he graduated in 1865.

That same year, he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister and also married Rosa Stevenson, a Presbyterian minister's daughter, on October 10, at Manhattan's historic Brick Church.

New York, both the city and the state, was his base during his first years out of seminary. He received his first posting to the Eighty-fourth Street Presbyterian Church — now known as West-Park Presbyterian Church — where he held forth with fiery sermons and espoused a conservative doctrine. He moved on to churches in Nyack and then Brooklyn.

His reputation as a teacher and theologian and his popularity as an after- dinner speaker grew rapidly, according to the Princeton University publication, The Presidents of Princeton University, which can be read on the university's website: "Even those who disagreed with his rigid conservative Presbyterian views admired his intellect and wit."

Conservative

Patton was championed by conservative Presbyterians, who were opposed to liberal views of religion that were emerging around the late 1800s.

When millionaire and conservative Presbyterian Cyrus McCormick established a chair in didactic and polemical theology at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Chicago, Patton was appointed to the post in 1872.

While living in Chicago, Patton continued to do battle against the forces of modernism. In 1874, he brought charges of heresy against a minister, Rev. David Swing, whose liberal views alarmed him. Patton led the prosecution team in the case that ended with Swing's acquittal by the church's general assembly.

Nonetheless, Patton emerged the real winner. When he threatened to appeal, Swing resigned from the Presbyterian Church. Patton continued his rise up the church's hierarchy. He wrote several books, beginning with The Inspiration of the Scriptures, published in 1869.

He was editor of a church paper The Interior from 1873 to 1876. In 1878, he was elected moderator of the church's general assembly.

Philosophy

In 1881, he moved back to New Jersey to become a professor at his alma mater. He taught ethics and philosophy of religion at Princeton Theological Seminary and in 1884, he accepted an offer to also teach the same subjects at the College of New Jersey (the College was renamed Princeton University in 1896).

Seven years later, he was appointed president of Princeton, which had a long connection with the Presbyterian Church. Patton's appointment was not popular.

In an article in the Fall 2008 edition of The Bermudian, historian Duncan McDowall wrote: "Patton was another non-American and, more importantly, he seemed profoundly out of kilter with the needs of higher education in the new America. Modernism was obliging most American universities to equip their students with scientific, practical knowledge, not just a pleasant polishing in the arts.

"Indeed, many feared that Princeton was falling behind the times and was rapidly becoming a Presbyterian country club for the indolent sons of East Coast patriarchs."

Still, Patton contributed much to the university, overseeing its expansion, with the construction of new dormitories, a gym, library and auditorium. He increased entrance requirements and hired capable professors, among them Woodrow Wilson, a lawyer and future U.S. president, who succeeded Patton as Princeton's president.

Administrator

Patton also helped lay the foundation for Princeton's standing as a top flight academic institution, but on the other hand, as recounted in The Presidents of Princeton: "Faculty accounts indicate that Patton lacked initiative in important policy matters, resisted meaningful curriculum reform, and was lax in matters of discipline and scholarly standards — in short, as one colleague said kindly, he was 'a wonderfully poor administrator'."

Patton's strong point was his popularity with students. In 1906, they petitioned to have a dormitory named after him. And every year, Princeton's Class of 1891 sent Rosa Patton a birthday telegram.

Historian McDowall wrote that his legacy "was shaped as much by what he didn't do as by what he did."

"Students were still required to take Greek in an age that demanded more practical skills, and Patton resisted calls to establish a law school and a graduate school.

Woodrow Wilson, who was pushing for the law school, became so frustrated he threatened to resign."

Celebrations

The high point of Patton's tenure was presiding over the school's 150th anniversary celebrations in 1896, when its name was changed from the College of New Jersey to Princeton University. U.S. President Glover Cleveland attended the festivities.

Patton resigned in 1902 and was succeeded by Woodrow Wilson. Patton moved on to Princeton Theological Seminary, where he served as president until his retirement at age 70 in 1913.

Patton then moved back to Bermuda and into the family home, Carberry Hill, on Keith Hall Riad, Warwick where he welcomed prominent visitors from home and abroad, including Woodrow Wilson, Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King, Rotary International founder Paul Harris, and James Morgan, the Montreal department store magnate who owned Southlands Estate in Warwick.

Former Princeton students vacationing in Bermuda also dropped in at Carberry Hill. Patton, who was totally blind in his old age — wife Rosa was also blind—became known as the 'Grand Old Man of Bermuda'. He was routinely showered with tributes in the press on his birthday.

Education

Francis and Rosa Patton had seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Patton's son George, whom he controversially hired to be his personal secretary at Princeton, followed him home to Bermuda, where he served as director of education between 1914 and 1924 and also as a Member of Parliament. (George Patton had studied and taught at Princeton Theological Seminary and University and had also studied at the University of Berlin and Cambridge University.)

Patton died at King Edward VII Memorial Hospital on November 25,1932. Obituaries in the Bermuda and overseas media were generous in their praise. Flags at Princeton were lowered at half-mast. The New York Times called him "a brilliant theologian of the conservative school". The Times also said his tenure at Princeton was "distinguished by the breadth of vision and understanding and the keen perception of scholastic needs that marked the man."

The Bermudian magazine described him as "a mighty intellectual, a brilliant theologian, philosopher and speaker of mesmeric and tremendous power, and an inspiration to a morally confused world by reason of the perfect inner harmony of his life".

Obituaries in The Bermudian and The Royal Gazette also revealed a little known fact. President Theodore Roosevelt asked Patton to represent the U.S. at the First World War peace talks at The Hague, but he declined because he was not a U.S. citizen. (Patton's wife Rosa died in 1942 and her obituary was also carried in the New York Times, which noted her husband's tenure as Princeton and her popularity with visiting Princeton students.)

Legacy

Two writers who have assessed his legacy in recent times have given a more measured view of his contribution to Princeton than what appears in the university archives.

Hugh Kerr's profile 'Patton of Princeton', which ran in the Princeton Seminary Bulletin in 1988, noted that "he was something of an enigma in his own day, which, perhaps, explains why he has been mostly neglected in our day".

While Patton "could scarcely qualify as a vigorous chief executive", both Princeton University and the Theological Seminary "flourished during his tenure of more than twenty-five years," he wrote.

Wrapping up his assessment, Kerr noted: "But if I share little sympathy with Patton's formal theology, I must confess that as I studied him and got to know him as a person, I became increasingly attracted to him for what he was and for his long and dedicated devotion to Christian truth as he saw it."

McDowall, while noting Patton's shortcomings, said posterity has not been kind to a man "who in 1900 was possibly the best known Bermudian in the world."

He added: "Perhaps in these times when national heroes seem to central to Bermuda's identity, he should be better remembered."

Patton's name lives on in Bermuda at Francis Patton School in Hamilton Parish. A plaque pays tribute to him at Christ Church.

In 2007, Patton, along with educators Adele Tucker, Matilda "Mattie" Crawford, Edith Crawford, Millicent Neverson, May Francis Smith, all of whose careers were on island, was honoured with a 'Pioneers of Progress' commemorative stamp.

|