Although born and raised in Bermuda, Anglican clergyman Ernest Graham Ingham spent his entire working life overseas, mostly in the UK, but also in Sierra Leone, where he was Bishop for nearly 14 years. He was a white Bermudian who made a singular contribution to the community of black Anglicans in segregated Bermuda.

Ingham, who was known as Graham, was the inspiration for the establishment of the black-led Guild of the Good Shepherd, the Anglican church’s oldest lay organisation. He also laid the groundwork for a move to Sierra Leone by black Bermudian Frederick Edmondson. Edmondson began life in Sierra Leone as a missionary, and in 1903, he became the first black Bermudian to be ordained an Anglican priest.

Born into a prominent Paget family, Ingham was a son of Samuel Saltus Ingham, Speaker of the House of Assembly, and Margaret Leaycraft. He was schooled locally until age 15, when he was sent to Bishop’s College School in Lennoxville, Quebec, Canada to complete his high school education.

Clergyman

He continued his schooling in the UK, graduating from Oxford University with a bachelor’s degree in 1873 and a master’s in 1876. He was ordained a deacon in 1874 and a priest the following year. His first year as a clergyman saw him “doing parish work in the slums of Liverpool”. He was then attached to a church in Rugby. In 1878, he became secretary of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) In Yorkshire. The CMS, whose goal was to spread Christianity throughout Africa and Asia, would play a crucial role in his life’s work, and was responsible for his move to Africa.

Ingham was vicar of St. Matthew’s Church in Leeds from 1880 until 1883, the year he was appointed Bishop of Sierra Leone. The country was at the time a British territory and his appointment had to be approved by Buckingham Palace.

His posting to Sierra Leone came a year before the Berlin Conference, an event that saw European powers formalising their claim on territories in Africa, with no involvement from the people of Africa. Modern-day historians say the consequences for Africans were devastating.

Thrived

Ingham was the sixth bishop to serve in Sierra Leone—but it was no dream job. English missionaries viewed a posting to West Africa with dread because of the high death rate. Three of his predecessors had died in office within two years. At his own consecration as Bishop a friend commented: “Ah, well, we have seen the last of Ingham.”

But Ingham thrived in Africa. He would describe his time there as “one of the great opportunities of my life”.

Writing years later about his reasons for going to Africa, he said: “It was not surprising that, a Colonial myself, and brought up in the midst of people of African descent, who had formerly being held as slaves by the white people, I was attracted by this bit of work, to which I was to give fourteen years.”

Ingham was responsible not just for Sierra Leone, but for a much larger swath of territory that included Lagos, what was then the Gold Coast (now Ghana), and the Canary Islands. Although he threw himself into his work, establishing church-run schools and training local clergy, winning converts was an uphill battle.

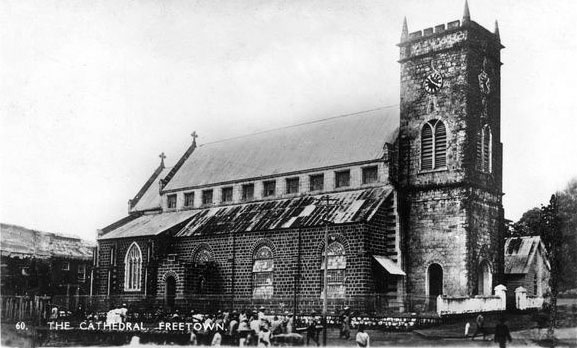

St. George’s Cathedral is said to be one of the oldest and grandest churches in Sierra Leone.

Missionaries

In late July 1895, after a 20-year absence, he arrived in Bermuda. The island was the last stop on a journey that had taken him to Antigua, Barbados and Jamaica. He was travelling under the auspices of the CMS and was on a mission: to recruit blacks to become missionaries.

Over the next month, he spoke at churches and community halls, to blacks and whites, but his message was directed at blacks. Addressing a packed house at Mechanics’ Hall on August 15, and aided by 19th Century visuals—a magic lantern that projected images of landscapes, houses and people—he urged black Bermudians to consider moving to the land of their ancestors to spread the gospel.

He spoke of the challenges whites faced in Africa: the climate and the fact that Africans would always regard the white man “as an enemy who wills them evil…” Although there were references to cannibalism, savagery and superstitions “of the natives”, Ingham went on to predict a great and glorious future for Africa.

Resigned

Ingham’s talks created much interest, but only Frederick Edmondson, a teacher who ran a school in Warwick and who had dreamed of becoming a missionary in Africa from boyhood, answered the call. Ingham organised his move to Sierra Leone. Edmondson resigned his teaching post and spent more than a year in Jamaica preparing for his new life.

But by the time Edmondson arrived in Sierra Leone, Ingham was back in the UK, a dispute with a local clergyman having ended his tenure. The two men were reunited in the UK in late 1897, when Edmondson was on his way to Sierra Leone. According to a report in The Royal Gazette, Ingham showed him “considerable attention”, but the two would never meet again.

Meanwhile in Bermuda, Ingham’s talks having resonated with black Anglicans, in 1896 members of the Anglican Cathedral established the Guild of the Good Shepherd to raise funds for Ingham’s church in Sierra Leone. The Guild became an important lay organisation and guilds at other Anglican churches on the island were established.

Emancipation

Michelle Simmons, in her book The Guild of the Good Shepherd and Bermuda’s Forgotten Anglican Missionaries, wrote that the Guild was similar to Friendly Societies that blacks formed during the post-Emancipation era. It provided black Anglicans with leadership opportunities during a time when the Anglican church was segregated.

By all accounts, Ingham’s tenure in Africa was successful, at least from the viewpoint of Anglican church leaders, but he would spend the rest of his life in the UK. He was rector of Stoke-next-Guildford from 1897 to 1904, was Home Secretary of the CMS until 1912, and finally vicar of St. Jude’s, Southsea.

In 1909, Ingham embarked on a nine-month world tour on behalf of the CMS that began in Canada and ended in India. He visited western Canada in 1912. Despite being from a large family—he was one of 11 children from his father’s two marriages—it does not appear he visited Bermuda again.

Author

Ingham was the author of six books, including Sierra Leone after a Hundred Years, From Japan to Jerusalem and Sketches in Western Canada. His portrait is in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

He and his wife had one son, Arthur Graham Ingham, but his line of direct descendants ended with his two grandchildren.

Like Ingham, Edmondson never returned to Bermuda. He spent the rest of his life in Sierra Leone. He married, had three sons, and moved up the church ranks to become Canon of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in 1934.

Given Ingham’s role in recruiting Edmondson, one is left wondering whether he made any attempt to maintain a connection with his fellow Bermudian, especially in light of his role with the CMS, which was responsible for missionaries. And if he did not, why not?

Edmondson was apparently denied the opportunity to relocate to Africa under the auspices of the CMS, which would have paid for return visits to Bermuda. Michelle Simmons writes that benefit would have been automatic for white missionaries.

Homecoming

For many years, members of the Guild of the Good Shepherd organised fundraisers for the church in Sierra Leone, but they eventually switched their fundraising focus on Edmondson. They sought to bring him home for a visit, although the much anticipated homecoming never occurred.

Ingham died in 1926 and Edmondson in 1940. In his Wikipedia bio, Ingham is described as “an eminent cleric”. An obit, reprinted in the Gazette, described him as “a most lovable man. One great charm and the secret of his influence was the remarkable way he was able to detach himself, for the time being from his own concerns and put himself entirely at one’s disposal. In these days of rush and self-centredness, even in the religious life, alas! this is far too rare a gift.”

|